The Dream Is Over, Pt. 1

Paul McCartney's Long and Winding Road

As the year winds down, I’m sharing some of my favorite pieces I’ve written about music for other venues in 2024. This one even has to do with Tolkien - tangentially! It is the first in a pair of essays about the Beatles’ breakup, as seen from each side of the Lennon-McCartney partnership. (You can read Part 2 here.) My hope is that, taken together, they have something novel to say about one of the most written-about moments in music history.

[NOTE ON SOURCES: Unless otherwise stated, I have relied on the incredible fan database The Paul McCartney Project for the historical information in this essay. See especially the entries for 1969-1971 in their documentary timeline.]

History looks inevitable in retrospect, but in the moment it is always in flux.

The Beatles’ breakup was not a forgone conclusion. There’s a heartbreaking sequence in Peter Jackson’s magnificent Get Back documentary[1] where Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr are the only members of the group to have turned up for a recording session on 13 January 1969. George Harrison has quit the band; John Lennon cannot be reached. Paul contemplates aloud the idea of announcing the Beatles’ breakup on live television, before finishing in quiet tears: “And then there were two.” Yet during a conversation two weeks later on the 29th, the day before the Rooftop Concert, John and George animatedly discuss the possibility of keeping the Beatles together while leaving space open for each member to pursue solo projects. Paul, of course, was never privy to this conversation. When Peter Jackson showed it to him in 2021, he was visibly moved: “I wish I knew that they had said that.” The afterimage of roads not taken.

It's not as though the road to that moment had been a smooth one. Since the Beatles stopped touring in 1966, Paul had become the group’s de facto leader and musical director. Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967) was his baby; so was Magical Mystery Tour (1967). It was Paul’s desire to get the band performing live again which prompted the Get Back project; and when that crashed and burned, it was Paul who helmed their swan song Abbey Road (1969). The other Beatles did not always take kindly to this – Paul could be domineering both in the studio and out of it. But by that point, everyone else in the band had already branched out into other creative ventures. Ringo took up acting; George escaped the shadow of the Lennon-McCartney juggernaut by hanging out with Eric Clapton and Delaney and Bonnie Bramlett; and John dove into politics and the avant-garde with Yoko Ono. Rising tensions in the group led all three of the other Beatles to quit at one point or another: Ringo in August ’68 during the White Album sessions, George in January ’69 during Get Back, and John in September of the same year following the release of Abbey Road.

As much as interpersonal tensions and creative differences weighed the band down, perhaps they might never have capsized were it not for Allen Klein. Since the death of their manager Brian Epstein in August 1967, the Beatles had demonstrated that however phenomenal they were as musicians, they were completely out of their depth where money was concerned. The formation of Apple and its unholy fusion of the band’s personal, creative, and business interests left them attending endless, infuriating administrative meetings and haemorrhaging cash. Klein, the Rolling Stones’ notoriously cutthroat manager, scented blood in the water after Epstein’s death. He sought to exploit the band’s money woes to commandeer the only band on earth bigger than the one he already managed.

Paul had always taken more of an interest in the business side of things than his bandmates, and as Apple’s financial situation grew more dire, he looked to his girlfriend Linda's father, the lawyer Lee Eastman, for guidance. Unfortunately, Klein had already convinced John Lennon that he would be the right man to repair the Beatles’ broken fortunes, and in a meeting on 28 January 1969—two days before the Rooftop Concert—he offered his services to the band. George and Ringo both agreed with John that Klein was the man for the job. Paul, immediately distrustful of the man’s boorish demeanor, walked out. Time proved Paul the wiser: Klein was a crook who bilked his clients out of millions. But in the moment, the other three saw Paul's plea to hire his girlfriend's dad as another expression of control freakery run amok. Klein became the Beatles’ manager by a vote of 3 to 1. Paul, meanwhile, was represented by the Eastmans. A house divided against itself cannot stand.

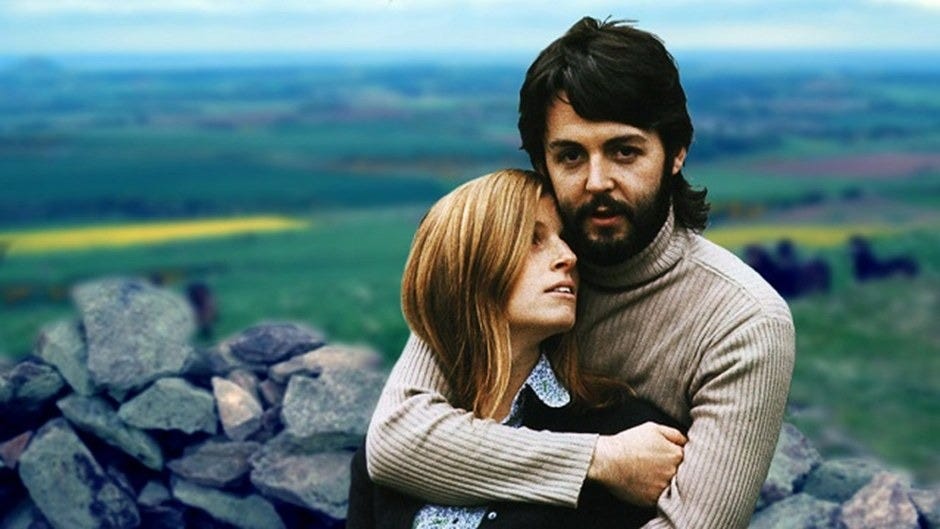

So as 1969 drew on, whenever he wasn't trapped in crazy-making negotiations with Apple and avoiding Allen Klein at all costs, Paul took refuge in the two loves of his life. The first of these was music, by which I mean "possibly the greatest album ever made," by which I mean Abbey Road. The second was his girlfriend and soon-to-be wife, New York photographer Linda Eastman. Paul and Linda had met back around the release of Sgt. Pepper in May 1967 but started dating in earnest during the summer of 1968. By 12 March 1969 they had embarked on a marriage that would endure for three decades. And as he struggled to hold the Beatles together—as a legal unit, as a creative partnership, as a band of brothers—Paul found that he preferred spending time with his wife, his adopted daughter Heather, and his new baby Mary on their farm in Scotland. Can you blame him? It was a welcome relief from the emotional and professional pressure-cooker that London had become for him.

When John quit the band for good in September of that year, the remaining members of the group agreed to keep his departure under wraps for the time being. But Paul wasn’t about to stop making music, and so in secret he began to work on his debut solo album, 1970’s McCartney. I could write an essay on the ramshackle delights of that record alone, containing as it does my single favorite McCartney solo song. (I'll bet you can guess which one.) For the purposes of this narrative, the LP is less important than the press release that accompanied its April 1970 release. Specifically this bit, as it became clearer and clearer as the release went on that McCartney represented a hard break from Paul’s past:

Q: Is your break from the Beatles temporary or permanent, due to personal difference or musical ones?

A: Personal differences, business differences, musical differences, but most of all because I have a better time with my family. Temporary or permanent? I don’t know.

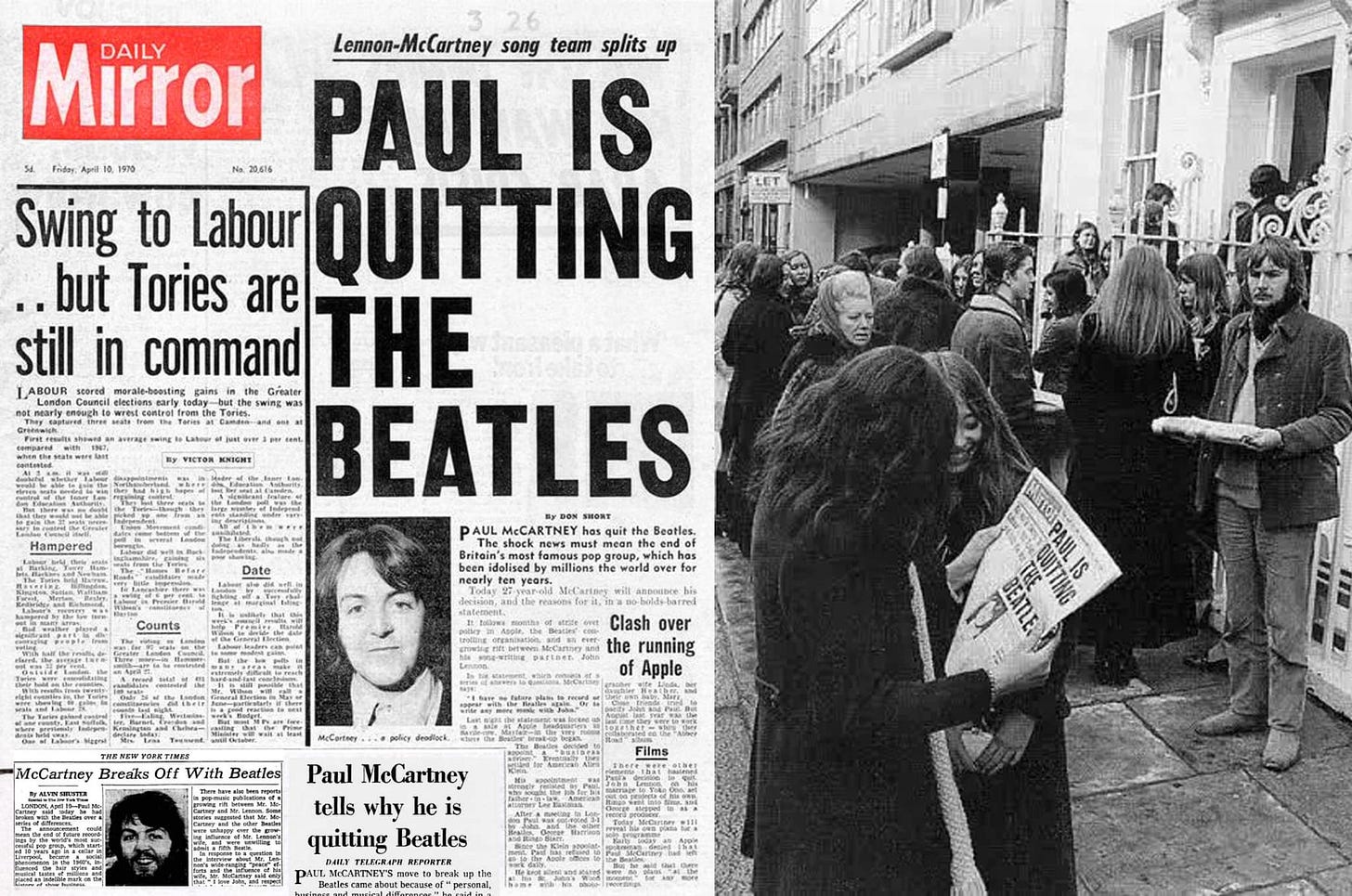

I mean, there it is. Yet even a record which Paul described in its press release as one about “Home, Family, Love” could not escape the whirlwind unleashed by the Beatles’ implosion. McCartney planned for the album to come out in mid-April 1970; Allen Klein and the other Beatles wanted him to postpone it so as not to interfere with the May release dates of the Let It Be album and film, respectively. Paul chose to ignore them; and on 9 April 1970, advance copies of McCartney went out to U.K. media outlets, history-making press release and all. On April 10th the headlines blared: “PAUL IS QUITTING THE BEATLES.”

In response to the deluge of media inquiries, Beatles publicist Derek Taylor put out another press release. I find it one of the most moving bits of music journalism ever penned.

April 10 1970

Spring is here and Leeds play Chelsea tomorrow and Ringo and John and George and Paul are alive and well and full of hope.

The world is still spinning and so are we and so are you.

When the spinning stops – that’ll be the time to worry. Not before.

Until then, The Beatles are alive and well and the Beat goes on, the Beat goes on.

John, George, and Ringo were as stunned to see the headlines as anyone. John in particular was furious that Paul had announced the breakup of his own accord. Instead of responding to the countless phone calls and requests for comment, Paul promptly fucked off to Scotland with his wife and his kids and his dogs. In the McCartney press release, he described Linda’s contributions to the album like this: “Strictly speaking she harmonises, but of course it’s more than that because she is a shoulder to lean on, a second opinion, and a photographer of renown. More than all this, she believes in me – constantly.” Paul and Linda adored one another, from the day they met until death did them part, 30 long years later. It is difficult to overstate how important summer 1970 was for them as they tentatively felt their way into a new life.

Yet in the back of Paul’s mind, he could not escape the question: What now? There could be no going back to the way things were before. It was blindingly clear that the Beatles needed to end, not just in name but in deed – and that meant ending in court. Could Paul do this “murderous thing,” as he later called it? Could he take his best friends, his brothers, and haul them before a London magistrate like parties in a messy divorce? The most legendary band to ever walk the earth, the partnership that had given his life meaning since the age of 15, the thing he had worked so desperately to hold together for years – could he just end it?

When he emerged from the Mull of Kintyre in September 1970, the path forward was clear. I will, again, hold off on discussing the musical project to which Paul next applied himself: the recording of Ram (1971), the bonkers (read: brilliant) follow-up to McCartney. Here's what I'll say for now: On New Year’s Eve, 1970, Paul McCartney filed with the London High Court to dissolve the Beatles. The trial began on 19 February 1971. In the days that followed, Paul would take the stand to testify that the Beatles were no longer a band in any meaningful sense of the word. On 12 March, the court found in Paul’s favor. The Beatles were no longer a functioning unit – and in consequence, Allen Klein was no longer their manager. Time magazine dubbed it Beatledämmerung, a riff on the Germanic epic Götterdämmerung: the Twilight of the Gods. From that day forward, Paul McCartney would be The Man Who Broke Up The Beatles.

No matter how many times I read about the breakup, it always gets me a little verklempt. All these years later, all these retellings later, the story still feels personal – because it is personal. It's a story of innocence giving way to experience, of youth’s soaring dreams ceding ground to the hard realities of change and loss. It's a story of growing apart from the people we love and finding new relationships that will sustain us in our next phase of living. Which is as much to say, it’s a story of growing up - of being human. For me, and for maybe for you too, the myth of the Beatles’ breakup is just that: a story that can help us make meaning out of our lives. And if that's true for fans like me, then what about the man who lived through it, for whom life and myth are fused?

But as someone once said, the great stories never really end: “We’re in the same tale still. It’s going on!” (You might say something similar about long and winding roads that go ever on and on.) No matter how much time passed, no matter how many albums he made, no matter how many hits he logged on the charts, Paul McCartney would never escape being a Beatle, any more than the rest of us can escape our own pasts. We can, however, learn to bear them gracefully. Paul would carry on writing and recording and living and giving the world his gift of song. And so, dear friends, we too will have to carry on. The dream is over - but the Beat goes on, the Beat goes on, and so does he, and so do we.

Thank goodness.

[1] The best film Peter Jackson has made since The Fellowship of the Ring (2001). That’s right, I said it!

I absolutely agree with the "best PJ film since...", though maybe not FotR.

I'll have to think about it as eleven oscars do tend to distract from the subject at hand... 😇