Lately I’ve been sharing some of my favorite pieces I’ve written about music for other venues in 2024. To wrap things up, here’s the second in a pair of essays about the Beatles’ breakup as seen from each side of the Lennon-McCartney partnership. (You can read Part 1 here.) My hope is that, taken together, they have something novel to say about one of the most written-about moments in music history.

In an advance press packet for his self-titled solo album on 9 April 1970, Paul McCartney announced that he was no longer working with the Beatles. Bombarded by phone calls and press inquiries, the band’s publicist Derek Taylor penned one of the most eloquent press releases in the history of popular song:

April 10 1970

Spring is here and Leeds play Chelsea tomorrow and Ringo and John and George and Paul are alive and well and full of hope.

The world is still spinning and so are we and so are you.

When the spinning stops – that’ll be the time to worry. Not before.

Until then, The Beatles are alive and well and the Beat goes on, the Beat goes on.

As news of the breakup hit the music world like a blast of TNT, John Lennon and Yoko Ono were in London screaming their heads off.

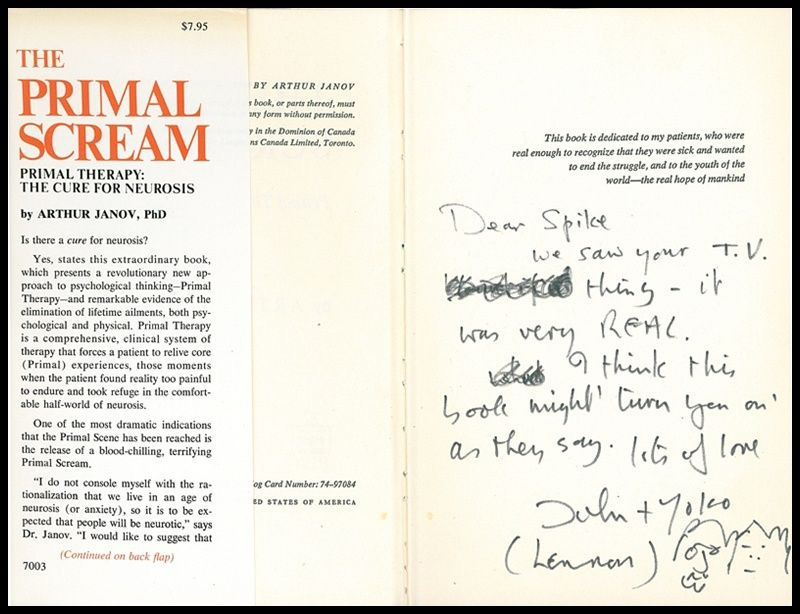

John had already quit the band in September 1969, though all parties had agreed to keep it under wraps. Not long thereafter, he received an advance copy of a book entitled The Primal Scream: Primal Therapy, the Cure for Neurosis by the psychotherapist Arthur Janov. He theorized that patients could heal their insecurities and dysfunctions by emotionally reliving childhood trauma. “[T]he child […] cannot be what he is and be loved,” Janov later wrote. “Primal Pains are the needs and feelings which are repressed or denied in consciousness. They hurt because they have not been allowed expression or fulfilment.” As the patient ventured into the subconscious, they were encouraged to release that pain bodily: writhing on the floor, weeping uncontrollably, and—yes—screaming.

John explained the process in his legendary 1970 Rolling Stone interview: “Primal therapy allowed us to feel feelings continually, and those feelings usually make you cry. That’s all. Because before, I wasn’t feeling things, that’s all. I was blocking the feelings, and when the feelings come through, you cry. It’s as simple as that, really.” Over the course of spring and summer 1970, he and Yoko underwent months of intensive primal therapy under Janov’s supervision. More than five decades later, there’s little evidence that primal therapy is clinically effective for the vast range of mental and physical issues Janov claimed it was. (Including, troublingly, homosexuality.) But it had a profound impact on John. For during those months of controversial therapy, and in the months following, he was picking up the pieces of a broken psyche and assembling them into the songs for his first album as an ex-Beatle: John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band.

‘Mother’ lets us know that this won’t be another Sgt. Pepper. A funeral bell tolls three times, then the next sound we hear is John’s voice: “Mother, you had me, but I never had you…” The song is a direct confrontation with his heretofore-buried sense of abandonment by his parents, especially his mother Julia. The arrangement is similarly direct, stripped back to Ringo Starr’s drums, Klaus Voorman’s bass, and John’s own piano so as to leave the vocals front and center. And as for John’s performance, I don’t know if anything like it had ever been heard on a rock record before. I have a two-year-old and a three-year-old at home: wails of “Mamma don’t go, Daddy come home” are not uncommon. This isn’t just Mum and Dad going to work though, to return at the end of the day. You can’t cry your mother back from the dead. This is John’s inner child howling across the abyss of death, demanding the impossible: a different past. ‘Mother’ is almost too vulnerable, as if you’ve accidentally drawn back the curtain on something that ought to remain unseen. Yet John has put his pain on full display, transforming primal scream from a private therapy to a public revelation. It’s one hell of a way to start an album.

It would be unendurable to dwell in such anguish over the course of an entire album, and John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band has other corners of the psyche to explore. ‘Mother’ nevertheless sets the table for the ten songs that follow, sounding the depths out of which this material is emerging. ‘Hold On’ eases off the pressure with a tuneful plea for first John, then Yoko, then the world to hang in there: things look bleak right now, but a better life is possible. ‘I Found Out’ on the other hand is the sound of disenchantment made manifest. Backed by a snarling proto-punk groove with the distortion turned up to 11, John takes aim at idols from stardom to the masculine ego to “religion from Jesus to Paul” (surely not an accidental juxtaposition). ‘Working Class Hero’ is the kind of song Roger Waters would perfect with Pink Floyd, a withering attack on the social and political rot that gives rise to dysfunction and despair, set to hypnotic folk guitar. ‘Isolation’ trades in the guitar for piano to compassionately address the individual who has been cornered by loneliness: “You’re just a human, a victim of the insane.” ‘Remember’ on the other hand peers back into the memories unlocked by primal therapy, seesawing between dissonance and consolation before abruptly combusting in its final seconds.

What emerges from the wreckage is the sound of producer Phil Spector’s piano, fading in from the edge of hearing. ‘Love’ is a song which I find beautiful beyond my ability to express. The words are simplistic, almost childlike: “Love is real, real is love, love is feeling, feeling love, love is wanting to be loved.” In that respect it’s a lot like ‘Mother’, but with a key difference. The power of that song consists in exposing the agony of abandonment. Here John embraces the terrifying intimacy of knowing and being known, holding out the possibility that maybe he—and by extension, we—can give and receive genuine, lasting love. It makes me cry.

‘Well Well Well’ couldn’t be more different, a fusion of the fuzzed-out blues guitar of ‘I Found Out’ with the political consciousness of ‘Working Class Hero’ and the confrontational screams of ‘Mother’. Then comes ‘Look at Me’, one of a trio of yearning acoustic ballads including ‘Julia’ from The White Album and ‘Oh My Love’ from Imagine, all based around a common guitar pattern. If John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band could be summed up in a single lyric, it might be this: “Look at me, who am I supposed to be?” It captures what makes these songs so remarkable. John Lennon the Beatle, one of the most famous human beings of the past century, might not seem like the most relatable person in the world at first glance. But by turning inward to his own emotions and insecurities, then turning outward to the world, teetering on the edge of arrogance and crippling insecurity, love and rage, hope and cynicism, he gives voice to something deeply personal yet universal at the same time. These dynamic tensions, these dialectical contradictions, build to a crescendo on the song which joins ‘Mother’ and ‘Love’ as one of John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band’s three thematic pillars: ‘God’.

In his classic Rolling Stone interview, John said: “Pain is what we are in most of the time, and the bigger the pain, the more gods we need.” You may not agree with John's theology here. But as every song on this album makes plain, in 1970 he was in a lot of pain – and he'd been putting his faith in a lot of idols to compensate. For the first time in his adult life he had cracked open his fragile ego to confront the trauma of his mother’s death, his father's desertion, and the fear of abandonment which had taken root in his psyche, structuring his sense of self in ways deeper than conscious thought. In so doing, he was forced to reckon with the ways in which he had inflicted that repressed trauma on others as a misogynist, an addict, an abusive partner, an absentee father. And in the midst of all that, the band that had given him a sense of meaning and purpose and belonging since he was a teenager—the band whose legend had come to overshadow his own personality—was over. His relationship with his creative partner, his best friend, his musical soulmate, was over.

‘God’ is John standing in the ruins of his old identity, self-deceptions and false gods strewn at his feet, and asking himself: What do I believe in now? Well, he doesn’t believe in magic, he sings as Billy Preston’s gospel piano pounds and Ringo’s drums thunder. He doesn’t believe in I-Ching either. The litany rolls on like a river swelling to flood: not the Bible, nor tarot, nor Hitler, nor Jesus, nor Kennedy, nor Buddha, nor mantra, nor Gita, nor yoga, nor kings, nor Elvis, nor Zimmerman (Bobby that is), until at last the dam bursts:

I don’t believe in Beatles

I just believe in me

Yoko and me

And that's realityThe dream is over

What can I say?

The dream is over

Yesterday

I was the dreamweaver

But now I'm reborn

I was the walrus

But now I'm John

And so dear friends

You’ll just have to carry onThe dream is over.

I submit this for your consideration as the finest vocal performance of John Lennon's career. It's breathtaking and heartbreaking, resigned and hopeful all at once. Here is where John plants his flag; by this he will stand or fall. And then, as the echoes of that declaration fade away, we hear the voice of a frightened child singing a nursery rhyme to fight back the tears: 'My Mummy’s Dead’. The album ends as it began: without compromise.

To say that the Beatles were more than the sum of their parts is the hackiest cliché in rock criticism. That’s because it’s true, of course. Yet the Beatles could never have made John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band. Can you imagine Paul McCartney adding vocal harmonies to ‘Mother’? Let alone ‘God’, which only makes sense in his absence. The man is a genius and I love him to death, but his presence would have made this album worse not better. That doesn't mean John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band is "better" than the Beatles - in my humble opinion, nothing is "better" than the Beatles. But it is different. John’s wrestling-match with himself, his traumas and insecurities, his dreams and fears, could only have taken place this side of the breakup.

Whether that was a fair trade is up to the listener. The skeletal, nerve-ending-raw sound of John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band is not to every fan's taste. Neither is its relentlessly personal subject matter. Some have called it self-absorbed, self-indulgent, solipsistic. It is, at times, all of those things. It is also stunning. Imagine is understandably John's most beloved work as a solo artist. John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band is his most important. It's a signal achievement in the history of rock n' roll, the last truly revolutionary album John Lennon would ever make. There's nothing else quite like it.