Imagine Peace Piece

The Art and Activism of John Lennon and Yoko Ono

[Author’s Note: I’ve not had a chance to blog much in 2024, but I have written a number of deep-dive essays for a music discussion group I co-moderate on Facebook. Some of them intersect with my research on Tolkien and religion; some are just pieces I’m especially pleased with. This is one of the latter. I hope you enjoy it, even as a detour from my usual material!]

On 4 February 1972, U.S. Senator and unrepentant segregationist Strom Thurmond sent a memo to President Richard Nixon. As chairman of the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee, Thurmond had reviewed FBI intelligence on one John Winston Lennon. Lennon and his wife Yoko Ono had conspired with antiwar agitators Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin to organize a major concert tour for 1972. Lennon biographer Jon Wiener explains the reasoning behind the tour:

The idea was to combine rock music with political organizing and do voter registration at the concerts. This seemed particularly promising in what would be the first election in which eighteen-year-olds had the right to vote. Everyone knew young people were the most antiwar constituency, but also the least likely to vote. The first US concert tour by one of the ex-Beatles would have been a huge event.

They did a trial run in Ann Arbor, Michigan, in December 1971. John and Yoko played with a new band, and fifteen thousand people heard speeches from Rennie Davis, Jerry Rubin and David Dellinger of the Chicago Seven trial, and Bobby Seale of the Black Panthers. Allen Ginsberg chanted a new mantra, and surprise guest Stevie Wonder played “For Once in My Life” and then gave a brief speech denouncing Nixon. It was a triumph.

Senator Thurmond and the FBI thought so too - but they were less enthusiastic about a traveling antiwar extravaganza that might galvanize young voters to cast their ballot for Nixon’s opponent George McGovern. In his memo to the president, Thurmond proposed a way to stop this renegade Englishman from interfering in U.S. politics: “deportation would be a strategic counter-measure.” So that’s exactly what the White House did. The remaining tour dates were cancelled and John spent the next three years in court, fighting for his right to remain in the United States.

John Lennon had not always been the outspoken advocate he was in the early 1970s. But he had grown up in Liverpool, a working-class town if ever there was one, and that inculcated certain countercultural values in him from an early age: a mistrust of authority, an abhorrence of snobbery, and a sharp-edged wit to cut through classist pretensions. Those personality traits would come in handy when he became one of the icons of the Sixties counterculture and its rejection of all things repressive and stuffy and old.

The Beatles were early opponents of the Vietnam War, denouncing the conflict as early as 1966 when only a third of the American public agreed with them. A year later, John’s song 'All You Need Is Love’ became a hippie anthem. But it was his budding romance with Yoko Ono, herself a longtime member of the artistic and political avant-garde, that would bust open his social consciousness. You can hear it cropping up in Beatles songs like ‘Revolution' (all nine of them) and ‘Come Together’. It was John and Yoko’s 1969 Bed-Ins for Peace, first in Amsterdam and later in Montreal, that solidified them in the public consciousness as international peaceniks.

Conceived as a kind of playfully avant-garde provocation akin to Yoko’s performance art, the Bed-Ins gave birth to ‘Give Peace a Chance’, John’s first solo single. But the events themselves met with mixed reactions from activists on the ground. There’s an uncomfortable video where New York Times war correspondent Gloria Emerson confronts Lennon and Ono with what she considers their frivolity and shortsightedness. She had reported from Vietnam as well as the Troubles in Northern Ireland, and she thought the Bed-Ins looked a lot more like a publicity stunt for the John and Yoko Show than a serious attempt at opposing the war. John is combative in the interview, but perhaps he had Emerson’s crtique in mind when he became more concretely involved in the following years.

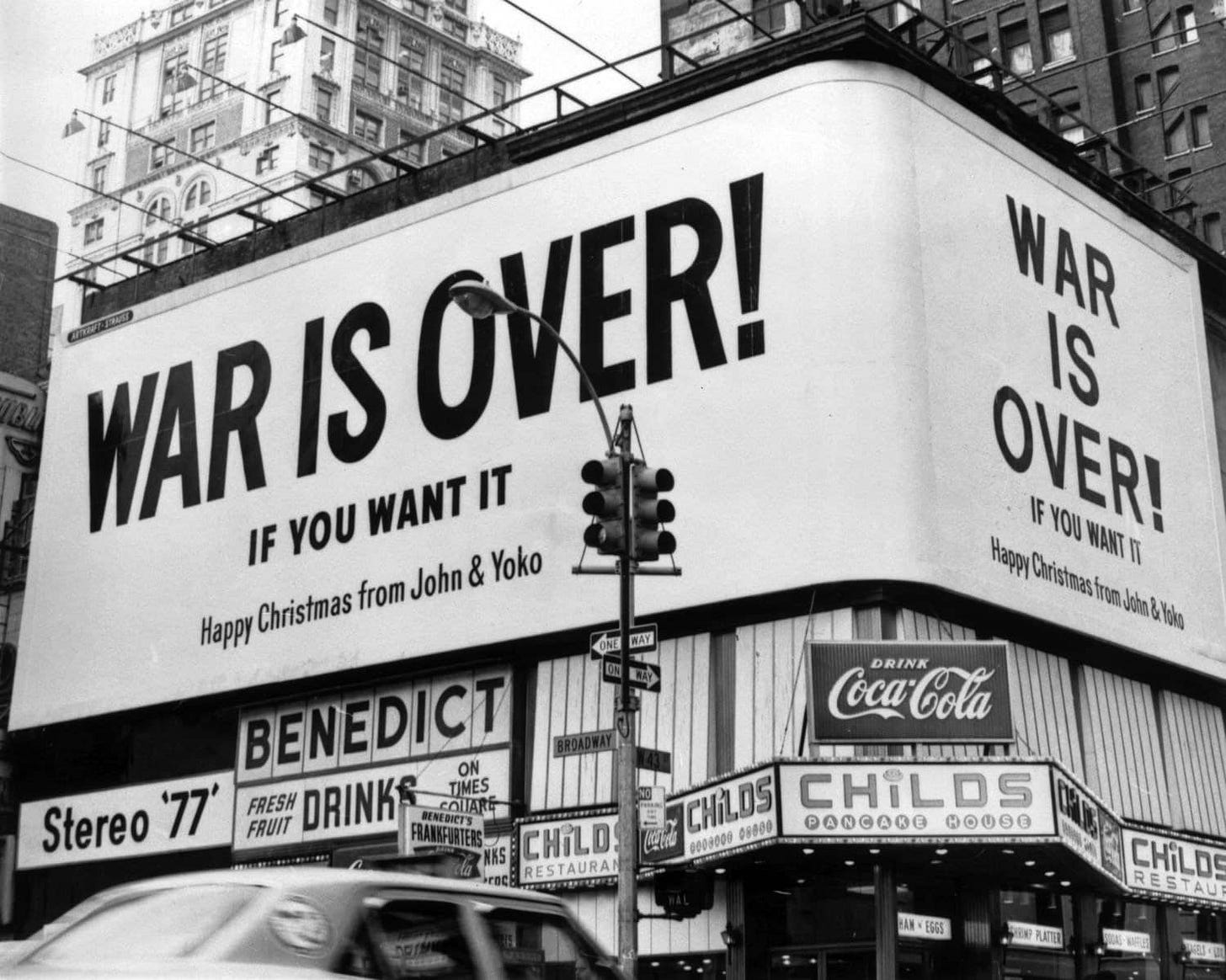

Over the course of the late 1960s and early 1970s, John wrote a series of protest songs which became anthems of the peace movement: ‘Give Peace a Chance’, ‘Working Class Hero’, ‘Instant Karma’, ‘Power to the People’, ‘Imagine’, ‘Happy Xmas (War Is Over)’, ‘Mind Games’, ‘Gimme Some Truth’. Antiwar demonstrators chanted his words on the National Mall in Washington D.C. on May Day 1971, when the Nixon administration arrested 12,000 demonstrators – the largest mass arrests in U.S. history. The track list of 1972’s Some Time in New York City is ripped straight from the headlines, as John strikes out at the Bloody Sunday massacre in Northern Ireland, the imprisonment of poet John Sinclair, and the trial of Black Panther Angela Davis with all the subtlety of a cinder block lobbed through a plate glass window.

One of Yoko’s most profound influences on John, personally as well as politically, was bringing him around to feminism and the sexual revolution. The same upbringing that had given John his populist edge had also taught him some pretty vile male chauvinism. Yoko was a strong, successful woman and artist in her own right long before she met John, and she had little time for his bullshit. Her refusal to put up with his sexism, and the change her self-possession wrought in his perspective on women, is reflected in calls for liberation in songs like ‘Power to the People’, ‘Well Well Well’, and the unfortunately-titled ‘Woman Is the N***** of the World’.

Yoko’s influence on John was also felt in the cosmic, kooky political theatre to which the two were prone. When John was ordered to leave the U.S. within 60 days in March 1973, he and Yoko declared the founding of their own “conceptual country”:

We announce the birth of a conceptual country, NUTOPIA.

Citizenship of the country can be obtained by declaration of your awareness of NUTOPIA.

NUTOPIA has no land, no boundaries, no passports, only people.

NUTOPIA has no laws other than cosmic.

All people of NUTOPIA are ambassadors of the country.

As two ambassadors of NUTOPIA, we ask for diplomatic immunity and recognition in the United Nations of our country and its people.

The “international anthem” of Nutopia was, appropriately enough, four seconds of silence. It’s ridiculous by design, edging the line between seriousness and silliness that characterized much of the couple’s activism. Take it all together, though, and it’s not hard to see why the Nixon White House served John with that deportation notice: he was lending his enormous star-power to some subversive causes.

John finally won his immigration battle in 1975, earning him the right to remain in the U.S. as a permanent resident. By then, however, his revolutionary fire had cooled. When Rolling Stone asked him to comment on the decline and fall of Richard Nixon, John admitted, “I’m even nervous about commenting on politics. They’ve got me jumpy these days.” In the same interview, he expressed conflicted feelings about the influence politics had had on his music: “It almost ruined it, in a way. It became journalism, not poetry.” Not long thereafter he left the public eye entirely to become a househusband and stay-at-home dad for his son Sean.

When he finally returned to the spotlight in 1980, John reaffirmed his ambivalence in an interview with Newsweek: “That radicalism was phony, really, because it was out of guilt. I’ve always felt guilty that I had money, so I had to give it away or lose it. I don’t believe I was a hypocrite. When I believe, I believe right to the roots. But being a chameleon, I became whoever I was with.” Many people go through a radical phase when they’re younger. For others it’s not a phase at all, but a lifelong commitment to change. But I also know that John tended to disavow his past in favor of his present, and not always fairly. In any event, he never lived to make peace between politics and domestic bliss; within months of that interview he was dead.

Today, pop culture looks back on John Lennon through rose-tinted glasses, painting him as a kind of secular saint. But he would be the first to admit he wasn’t always a peaceful man. “I fought men and I hit women,” he told Playboy in 1980. “That is why I am always on about peace, you see. It is the most violent people who go for love and peace. Everything's the opposite. But I sincerely believe in love and peace. I am a violent man who has learned not to be violent and regrets his violence.” John’s mysogny and abuse weren’t acceptable at the time, and they aren’t acceptable now. Likewise, I’m hardly the first person to observe the irony in a world-famous millionaire asking his listeners to “imagine no possessions” from behind an ivory-white piano in his Tittenhurst mansion.

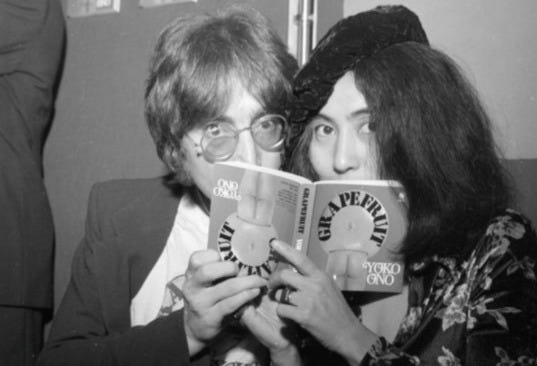

However, I would like to reframe ‘Imagine’ as less of a political manifesto and more of a conceptual art project. We now know that Yoko, not John, wrote most of the lyrics to ‘Imagine’ – she’s been given a long-overdue credit on newer releases of the track. They have much in common with her 1964 art book Grapefruit. The book is full of unconventional thought experiments like ‘CLOUD PIECE’:

Imagine the clouds dripping.

Dig a hole in your garden to

put them in.

Or ‘SNOW PIECE’:

Think that snow is falling. Think that snow is falling

everywhere all the time. When you talk with a person, think

that snow is falling between you and on the person.

Stop conversing when you think the person is covered by snow.

Here’s another one, called ‘Painting to be constructed in your head’:

Go on transforming a square canvas

in your head until it becomes a

circle. Pick out any shape in the

process and pin up or place on the

canvas an object, a smell, a sound

or a colour that came to your mind

in association with the shape.

In each case, the art isn’t the words on the page. It only exists when the reader thinks it into being and acts it out. Yoko and her audience co-create the work through a shared act of imagination.

This, I would argue, is what is happening with ‘Imagine’ too. It speaks to the most enduring aspect of John and Yoko’s art-as-activism: its capacity to jolt us out of conventional ways of thinking and conceive a different world. Whether the radicalism was “phony” or not is something of a moot point. The question is, does the music hold up? Does it still spark out imaginations?

I would answer yes. In the decades since his death, John's activist image has been burnished into a brand, complete with bumper stickers and graphic tees and misattributed quotes. The real John Lennon could be idealistic to the point of naïveté; he could confuse self-publicity with raising awareness for the cause; he could be anything but peaceful. But in his best moments, John was capable of channelling the yearning for love and justice into songs that speak directly to that part of the human spirit that believes in a tomorrow that’s better than today. That’s something we could use more of in a world that is, by most metrics, getting worse. So in 2025, imagine that we did give peace a chance. That war could be over, if we wanted it. That love was the answer, and we knew that for sure.

You may say I’m a dreamer, but—well, you know how the song goes.

Another fascinating piece. Keep 'em coming.... :-)

"We" has to include some awfully unlikely players if that's going to work. It needs but one foe to breed a war, not two, Master Warden...