All You Need Is Collective Effervescence

The Beatles and (Non)religion at the End of the Sixties

[Author’s Note: I’ve not had a chance to blog much in 2024, but I have written a number of deep-dive essays for a music discussion group I co-moderate on Facebook. Some of them intersect with my research on Tolkien and religion; some are just pieces I’m especially pleased with. So from now until the end of the year I’ll be sharing a few of them. I hope you enjoy them, even as a detour from my usual material!]

…

In 1967, mere months before the release of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and the Summer of Love, sociologist Thomas Luckmann published a little book entitled The Invisible Religion. In it, he argued that, as fewer and fewer people identified as Christians in the Western world, people would begin turning to other cultural resources to meet their needs for identity, community, and meaning. This might be anything from membership in a political party to a person’s favorite movie star, from Eastern mysticism to comic book heroes. Instead of everyone belonging to one overarching religious tradition, modern Westerners would begin—were already beginning—to personalize their individual spiritualities (or lack thereof). In place of shrines to saints, shrines to Elvis; in place of church services, rock concerts; in place of the Eucharist, yoga in the park.

The Beatles ascended the heights of popular stardom smack dab in the middle of this transformation.1 The wild response to their concerts is a textbook definition of what Émile Durkheim called collective effervescence: that chills-down-the-spine overflowing of emotion that comes when a bunch of people get together and direct their energy and attention toward a single, powerful object. The object, in this case, being our four ladsfrom Liverpool. That’s not to say the Beatles were a “replacement” for Christianity or Judaism or what have you; they had and still have plenty of religious fans.2But speaking personally, my love for them has definitely verged at times on a spiritual experience. I never understood why teenagers lost their minds during Beatlemania until I saw Paul McCartney with 50,000 of my closest friends at Boston’s Fenway Park in 2013. Now I know.

You can see, then, why John Lennon could say in March 1966, with no intention of causing offense, “We're more popular than Jesus now; I don't know which will go first – rock 'n' roll or Christianity.” You can see why so many American church leaders were incensed: they were worried that, at some level, he might be right. And you can see why, less than six months later in August 1966, the band called an indefinite halt to live performance. You can only handle so much collective effervescence, so much of people projecting their dreams and desires all over you, before you either go mad or start a cult. Maybe both.

Paul McCartney later said of this time: “We’d tried for it not to go to our heads and we were doing quite well – we weren’t getting too spaced out or big-headed – but I think generally there was a feeling of: ‘Yeah, well, it’s great to be famous, it’s great to be rich – but what it’s all for?'” And so, singly and as a group, the Beatles began to explore spirituality. They did this in two major ways: through the LSD-laced ethos of the hippie counterculture, and through Eastern mysticism.

Tom Wolfe, author of The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (1968) about Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters, viewed the hippies as a kind of neo-spiritual movement. Their gospel was freedom of expression, anti-establishment communitarianism, and commitment to “peace and love, peace and love.” (Oh, and drugs. Lots and lots of drugs.) The Beatles were of course one of the pioneers and popularizers of the counterculture, going back at least as far as ‘The Word’ on 1965’s Rubber Soul:

Say the word and you’ll be free

Say the word and be like me

Say the word I’m thinking of

Have you heard? The word is “Love”

“Love” here was clearly something other, something bigger, than the romantic attraction they’d been singing about up to that point. 1966’s Revolver is where their interest in spirituality—and lysergic acid—really took hold. Two key examples are George’s sitar-laced ‘Love You To’ and John’s recitation of acid guru Timothy Leary’s translation of The Tibetan Book of the Dead over the swirling psychedelic tapestry of ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’. The trend would continue through 1967 and Sgt. Pepper before culminating in ‘All You Need Is Love’. A suitable subject for history’s first worldwide satellite broadcast!

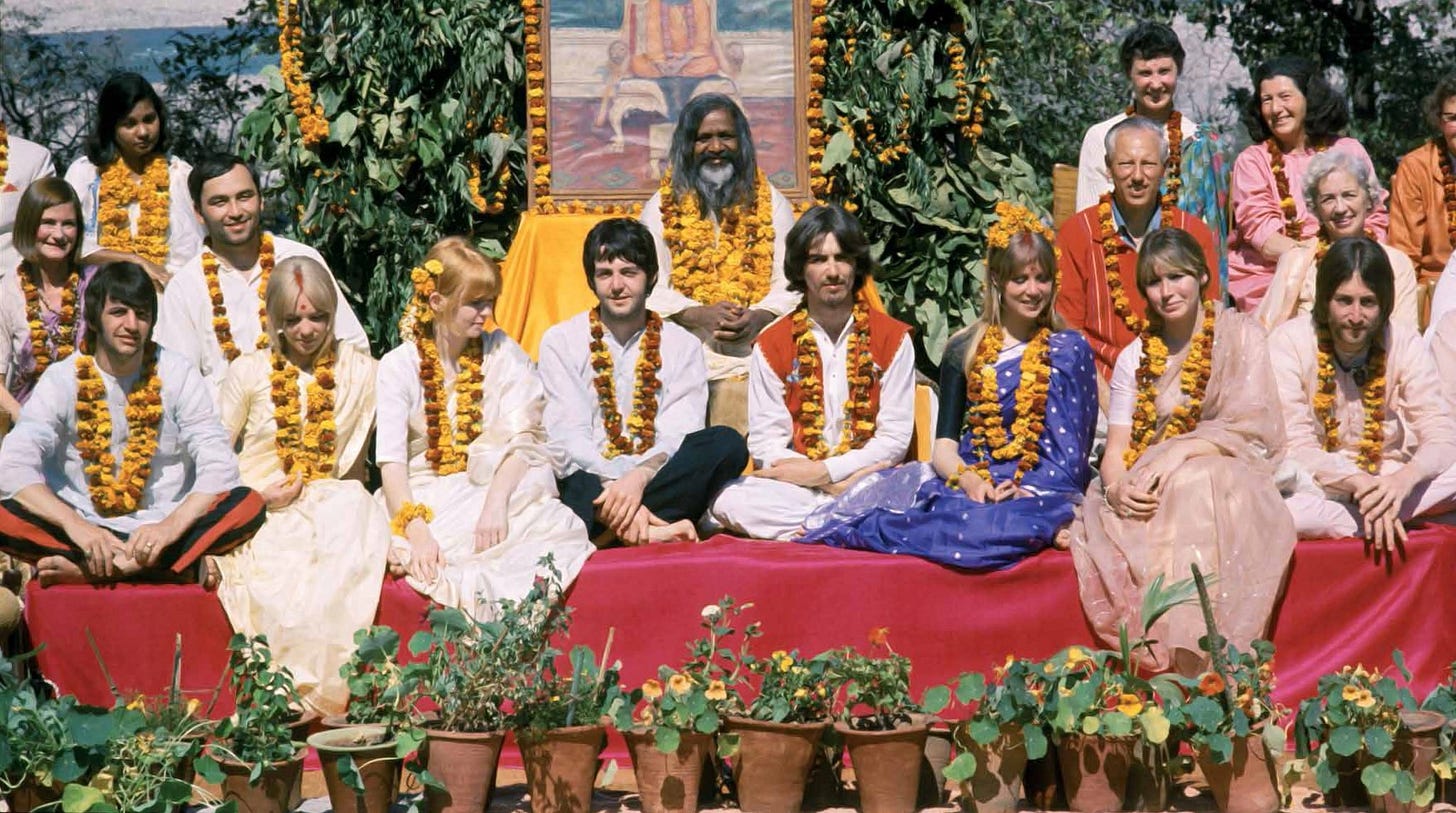

It was George Harrison’s burgeoning fascination with Indian music and mysticism that first brought the band into the orbit of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. Or really, I ought to say his wife Pattie Boyd’s: after a 1966 trip to India with George, she spotted a newspaper ad for classes on Transcendental Meditation back home in England. Based on the Harrisons’ shared enthusiasm for the Maharishi's modern take on Hindu Vedanta, the whole band headed to Wales for a ten-day meditation retreat in August 1967. Whilst there, they received news that Brian Epstein, their longtime manager and confidante, had died of an accidental drug overdose back home in London. John would later say that Epstein’s death was the beginning of the end for the band – but nobody knew that at the time. So after a few months grieving and putting their affairs in something resembling but not quite achieving order, the lads headed out to Rishikesh for an extended stay at the Maharishi’s ashram.

For the first time in years, the Beatles could escape from the pressures of stardom. They occupied themselves with meditation and vegetarian food, Indian garments and dharma talks, hanging out and playing guitar with Beach Boy Mike Love and Donovan and Mia Farrow on balmy evenings by the Ganges River. George told a fellow-visitor to the ashram: “I get higher [on meditation] than I ever did with drugs. […] It’s my way of connecting with God.” (Fun fact: while they were staying at the ashram, Apple Films director Denis O’Dell pitched the band on a film version of Lord of the Rings. John would play the role of Gollum.) The visit ended, famously, on a bum note: John, who otherwise found a lot of value in meditation, fiercely rejected the Maharshi after allegations that he’d engaged in sexual misconduct with one of his students. The band left with at least two important things: George Harrison’s growing commitment to Hinduism, and several dozen of the greatest songs of the rock era, many of which would find their way onto The White Album (1968).

One last thing: I would be remiss, when discussing the Beatles and religion, if I didn’t mention the woman whose spiritual universalism would profoundly influence her soon-to-be spouse: Yoko Ono. When John met her at an exhibition of her work in 1966, she was already something of a star in the avant-garde world. Take her now-famous work of conceptual art Cut Piece as an example. Yoko would invite an audience to witness her seated cross-legged in the middle of a room in the finest clothes she owned. The audience had scissors with which they were invited, piece by piece, to cut off her clothes. She didn't speak, but she would make eye contact with the audience-participants as they snipped away at her dress, her underwear, until she was fully naked. Call it pretentious if you like; I call it powerful, confronting a group of mostly White, mostly male museum-goers with their complicity in literally denuding a tiny Japanese woman. I don’t know if John ever witnessed a performance of Cut Piece, but he was smitten with its creator to put it mildly.

Just another cross-current in the maelstrom of collective effervescence and dawning disenchantment that was the late 1960s – for the Beatles, and for everyone else.

The same was true, I might note, of J.R.R. Tolkien. My own father went off to university in the late 60s with a vinyl copy of Sgt. Pepper in one hand and a Ballantine paperback of The Fellowship of the Ring in the other. Meanwhile, he left the Roman Catholicism of his childhood behind him.

That said, Beatles scholar Candy Leonard (2021) has characterized Beatles fandom a “de facto religion.” I might not go that far, but there are certainly parallels – which is, after all, a big focus of my current research!