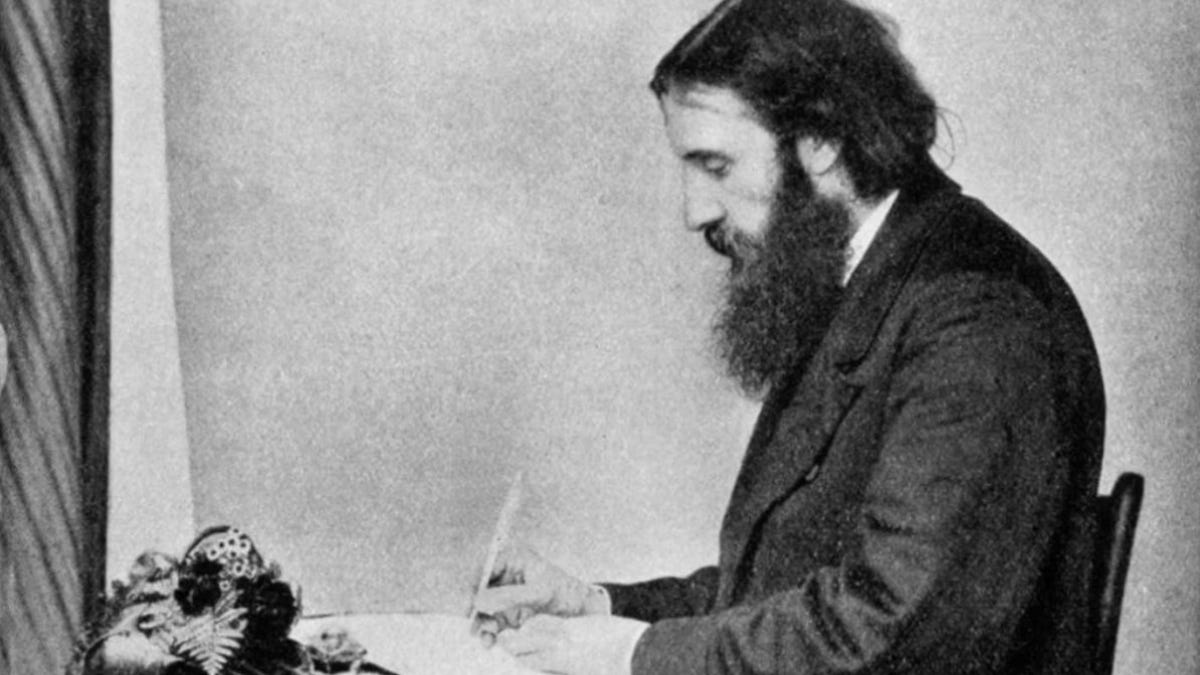

George MacDonald's Post-Christian Imagination

200 years since his birth, the great Scottish fantasist still enchants.

[Note: I wrote this paper for the George MacDonald Bicentennial Conference at the University of St. Andrews, 8-10 November 2024 and thought I would share it with all of you! For those unfamiliar: George MacDonald was a seminal Victorian fantasist who influenced both Tolkien and C.S. Lewis among others.]

According to 2022 census data, only 38.8% of Scots describe themselves as Christian, compared to 51% who describe themselves as nonreligious entirely. Compare this to as recently as 2011, when the ratio was 54% Christian to 36.7% nonreligious. Whether this trend in religious disaffiliation is good or bad depends very much on whom you ask – as a theologian and a Congregationalist minister, I am inclined to call it a little bit of both. Either way, it points up a tectonic shift in the contemporary spiritual landscape. It is difficult to pin down, with any precision, when the plates of Western societies began to grind in this direction. But born two centuries ago this very year, in the wake of the European Enlightenment, in the very midst of the Industrial Revolution, George MacDonald (1824-1905) straddled the fault-line of what we might call post-Christian secular modernity. “A society in which it was virtually impossible not to believe in God” has given way “to one in which faith, even for the staunchest believer, is one human possibility among others” (Taylor 2007, 3). We live in an inescapably pluralistic society; and in this essay I contend that MacDonald's notion of the fantastic imagination can serve as a foundation for the practice of theology in just such a society as this. Fantasy literature evokes meanings which cannot be reduced to propositions and can thus be understood in terms of what philosopher Charles Taylor calls multiple “underlying accounts” of their origins and significance. Fantasy is therefore uniquely suited, not just to Christian theology in a secular age, but to specifically post-Christian theology - as MacDonald’s own fantasy proves.

In his seminal essay “The Fantastic Imagination”, MacDonald passionately resists the temptation among readers of fairy tales to figure out what they are “really” all about. His imaginary interlocutor insists that a fairy tale surely must mean something, because the author intended it to mean something. Otherwise, why write the thing? MacDonald responds: “Everyone […] who feels the story, will read its meaning after his own nature and development” (2004, 66). Indeed, “It may be better that you should read your meaning into it […] your meaning may be superior to mine” (66). And this is as it should be: the purpose, he says, of “a genuine work of art” is not so much “to convey a meaning as to wake a meaning” (67). MacDonald’s example of a sonata is apt: music evokes powerful emotions—powerful meanings—but each hearer will articulate those meanings differently. “Has the sonata therefore failed?” he asks. “Had it undertaken to convey, or ought it to be expected to impart anything defined, anything notionally recognizable?” (67) Of course not. The meaning of a sonata is not reducible to a series of propositional statements which can be accepted or rejected for their truth-value. It is art not argument – and so also fairy tales. He says, “To ask me to explain is to say, ‘Roses! Boil them, or we won’t have them!’ My tales may not be roses, but I will not boil them” (69). If you’ll allow me to mix MacDonald’s boiling metaphor, there is an overflow of meaning in a fairy tale – which, as J.R.R. Tolkien would later point out, is any story about the enchanted realm of Faery (or Faërie), not just a story about “fairies” however defined (Smith of Wootton Major, 95). This kind of fairy tale intimates a sense of “something more” than what meets the eye, yet it does not define or delimit the something in question.

MacDonald’s essay aligns with Charles Taylor’s argument for the significance of art in a secular age. It is worth outlining, in brief, wherein this “secular age” consists, according to Taylor, so we can see how MacDonald fits into it. First and foundationally, the premodern Western world is enchanted: charged with spirits and non-human personalities. The self who navigates that world is porous, vulnerable to influence by these spirits for good and for ill. The porous self is defined in the context of a communal and cosmic order of which it is one small interlocking part; it is thoroughly embedded in geography, ecology, and society. By way of contrast, the modern Western self is buffered: the bounded, rational individual, disenchanted and disembedded. This ideal self is also excarnated: cut off from emotion, intuition, the body, and all those other pesky “nonrational” elements of human experience. The emergence of this buffered self is bound up with a change in the felt nature of time and space as well: once bound together in a sacred spiral, they are rendered homogenous and unilinear, resources to be deployed and exploited. These concurrent paradigm shifts result in what Taylor calls the immanent frame, which “constitutes a ‘natural’ order, to be contrasted to a ‘supernatural’ one, and an ‘immanent’ world, over and against a possible ‘transcendent’ one” (Taylor 2007, 542). Secularity thus involves not only a decline in religious belief, but a shift from a “transcendence perspective” of existence to an “immanence perspective.”

In his book Cosmic Connections: Poetry in a Disenchanted Age, released earlier this year, Taylor argues that in the wake of the “Romantic revolution,” art is one means of transgressing this immanent frame and re-enchanting the world. In prior ages, meanings were “out there” for us to encounter in the world; our identities and our communities were embedded in a purposive cosmic order which embraced the whole of life (41; cf. Taylor 2007, 345-346). (Or, at least, that was the idea, even if it was not always and everywhere the lived reality!) But with the emergence of Enlightenment rationalism, instrumentalized natural science, and global capitalist Empire, the Christian “cosmic orders” which underlay the enchanted world of Western premodernity grew increasingly unviable. The medieval Christian world-picture was no longer the only game in town, even for those who longed for connection to something beyond the immanent frame. Increasingly, Westerners lived “with a sense of loss, and with a corresponding aspiration to recover a contact with nature which the large-scale, successful application of instrumental reason was destroying” (TAylor 2024, 23). If art was to become a pathway for reconnection to the depth dimension of reality in a world whose meanings could no longer be taken for granted, then it needed to practice, in Taylor’s phrase, epistemic retreat. It needed to “bypass the philosophical objections to the belief in cosmic orders but generate in the reader the felt sense of a reality higher and deeper than the everyday world around us” (x). Such artworks “generate a powerful experiential sense of cosmic order but stop short of affirming the reality of these orders in the objective world beyond human experience” (x). This opens space for multiple underlying stories or underlying accounts of art’s significance. As with MacDonald’s example of the sonata, we can have a strongly grounded sense that something is meaningful but have widely divergent explanations for how and why. Such artworks, in Taylor’s words, are

grounded in the power of the experience, whereas the underlying story has to draw on beliefs about the universe, God, the Life Force, or human depth psychology, or whatever. […] That is why they can enjoy a certain independence from convictions about underlying realities, and why people of such different theological and anthropological persuasions could share a sense of [their] revealing power[.] (57)

And MacDonald’s fantasies are a case in point.

Let’s take the “The Golden Key” as an illustration. If you’ve not read what is perhaps MacDonald’s most celebrated fairy tale, I highly recommend it. It’s not long, little more than 10,000 words; it’s absolutely enchanting; and nothing I have to say in the next several paragraphs will make much sense without it. In his abandoned draft of an introduction to the story, Tolkien writes:

If you […] have read The Golden Key, you will not forget it. Something at least will remain in your own mind, as a beautiful or strange or alarming picture[,] and it will grow there, and its meaning, or one of its meanings—its meaning for you—will unfold itself, as you also grow. (Smith, 91)

For Tolkien, the “beautiful or strange or alarming picture” that stuck in his mind was the great faerian valley with its flint-hard mountains and its sea of shadow-shapes. For me it is the air-fish that ripples behind Tangle as she penetrates deeper and deeper into the enchanted forest, and her wordless wonderment when first she encounters the Old Man of the Fire:

For she knew there must be an infinite meaning in the change and sequence and individual forms of the figures into which the child arranged the balls, as well as in the varied harmonies of their colours, but what it all meant she could not tell. He went on busily, tirelessly, playing his solitary game, without looking up, or seeming to know that there was a stranger in his deep-withdrawn cell. Diligently as a lace-maker shifts her bobbins, he shifted and arranged his balls. Flashes of meaning would now pass from them to Tangle, and now again all would be not merely obscure, but utterly dark. She stood looking for a long time, for there was fascination in the sight; and the longer she looked the more an indescribable vague intelligence went on rousing itself in her mind. (MacDonald 1867, 52-53)

Like Tangle, what it all means I cannot tell; only that it touches something in me which, to quote Taylor, “bypass[es] philosophical objections” and “generate[s] […] the felt sense of a reality higher and deeper than the everyday world around us” (2024, x). The fact of the matter is, these images mean many things – and that is just as MacDonald would have it.

Bonnie Gaarden offers a double reading of “The Golden Key” as both a story of the soul’s journey toward God, and of Romantic individuation. On the first reading, Mossy and Tangle are types of the Christian and the non-Christian, respectively. With the Golden Key of faith, Mossy’s journey to “the place whence the shadows fall” is, while not painless, relatively direct (2006, 37-38). Tangle has no key, however, and so her journey is longer, ever downwards into deeper layers of the soul and the psyche as she wends her way toward communion (42). Yet it is significant that both Mossy and Tangle, “believer” and “nonbeliever” alike, make it there eventually. This reading brings out MacDonald’s Christian universalism (Prickett 2005, 159). Gaarden’s other, non-Christian reading traces the “spiral path” which Taylor identifies in the German Romantics who so influenced MacDonald: a movement from the unitive innocence of childhood into alienated self-consciousness, thence into a Romantic Bildung and ultimately a “higher unity” with Nature and with our true selves (2024, 7). Under this schema, Mossy’s relatively straightforward journey with key in hand can be read as a representation of that part of us which is always and already at one with the cosmos. Tangle’s arduous path, meanwhile, is our ego-self, our “Self-in-process who struggles and suffers without knowing her end” (Gaarden 2006, 45). Whichever reading you prefer, Gaarden concludes that while he was “a devout theist, but one who emphasized God’s immanence over God’s transcendence, MacDonald created literary images that can be read with or without reference to the Christian God” (36). “The Golden Key” is a golden example of fantasy written by a Christian author yet which nevertheless practices epistemic retreat, opening the door to multiple underlying accounts of the meanings which readers may find there.

Now, I wish at this point to make something clear. My guiding question in this discussion is not, “How can Christians effectively communicate their theology in a Western context which is no longer exclusively Christian?” This is a question of apologetics; or as Holly Ordway puts it, how do we “show the truth, coherence, power, and beauty of Christianity” when “[t]he very people who most need to hear the truth are often the ones most resistant to listening to us” (2017, ch. 1, location 172-263)? I take issue with this framing on grounds both aesthetic and theological. Aesthetically, the line between apologetics of this sort and allegory is a thin one, easily transgressed – and as MacDonald says, a writer “must be an artist indeed who can, in any mode, produce a strict allegory that is not a weariness to the spirit” (2004, 67). Theologically, it smacks of dissimulation, surreptitiously leading my readers to a particular variety of Christian belief without them noticing what I have done. This moreover restricts the meaning of quote-unquote “imaginative apologetics” to the author’s evangelical intent – and we have already heard how MacDonald feels about that. As Tolkien once said of The Lord of the Rings, “It is not ‘about’ anything but itself” (Letters, 220).

My guiding question is instead, “What are the theological affordances of fantasy as such?” Because fantasy literature, as we understand it today—with George MacDonald as one of its founding figures—is distinctively post-Christian. It depends on the reader’s knowledge of its own impossibility; and that depends, in turn, on some dominant consensus about what is possible in the first place (Saler 2012, 12-13). From MacDonald’s time up through ours, Western “consensus reality” has been characterized, at fundamental level, by the disenchantment which I invoked above. Modern fantasy depends on this dialectic of “disenchantment-reenchantment” for its characteristic literary effect. In the premodern West, the world was simply enchanted. There was no alternative, to paraphrase Margaret Thatcher’s famous dictum about neoliberalism. Now there are alternatives – there are multiple viable underlying accounts of reality. So what kind of theology can we do with a post-Christian form? Or perhaps better, what kind of theology does the form itself do?

Here, again, MacDonald can show the way. Brian Attebery writes that MacDonald’s “symbols are all plurisignificant: there is no one answer to the mystery” (2014, 77-78). This “plurisignificance” reflects MacDonald’s theological convictions regarding the nature of human creativity. Humans are, to use Tolkien’s later phrase, sub-creators, made in the image and likeness of a Creator (On Fairy-Stories, 66). Because we have to use God’s creations—not least our human body, mind, spirit, imagination—to sub-create in our turn, MacDonald writes, “A man [sic] may well himself discover truth in what he wrote; for he was dealing all the time with things that came from thoughts beyond his own” (MacDonald 2004, 69). In Attebery’s view, this is precisely what MacDonald himself did; for though he was a devout Christian, he did not hew rigidly to the old cosmic order in every respect. His first congregation in Arundel, Sussex drove him out on account of his heretical universalism. But “rather than giving up his flirtation with universal redemption, [he] wrote it into each of his major fantasies” (Attebery 2014, 76). Likewise, his stories are full of capable, powerful, even semi-divine female characters who challenge the patriarchal gender assumptions which pervade much of Christian theology. (“The Golden Key” is another case in point.) As Attebery puts it,

MacDonald trusted the truthfulness of fairy tales—both traditional Märchen and his own invented stories—and the symbols they cast up, including women rulers and adventurers. Where those stories and their inner logic diverged from biblical authority, he followed the former. (81)

For MacDonald, the act of writing fantasy does theology – one might even call it theopoetic, a co-creative making with God (cf. Walton 2020, 161). And if this is true for the writer, then surely it is also true for the reader whose “meaning may be superior” to that of the author whose religious commitments they may or may not share (MacDonald 2004, 66).

Taylor writes that art in a disenchanted age does not simply reconnect us to the static cosmic orders of yesteryear; it enables “the exploration of new meanings, previously uncharted” (2024, 66). Stephen Prickett says much the same thing about fantasy in particular: “Over the last two hundred years fantasy has helped us to evolve new languages for new kinds of human experience; it has pointed the way towards new kinds of thinking and feeling” (2005, 3). Among these “new kinds of human experience” which might give rise to “new meanings, previously uncharted,” I would add the experience of post-Christianity itself. The experience of a lifeworld caught in a dialectic of disenchantment and re-enchantment, in which the modern buffered self struggles to square the gains of modernity (individual freedom, social justice, modern medicine) with its failures (alienation, exploitation, ecocide). Two hundred years since his birth, George MacDonald remains a pioneer of fantasy literature as a mode, not only for theology for a post-Christian society, but for post-Christian theology. Such a theology evokes but does not evangelize. It offers glimpses of richer meaning and deeper enchantment than modernity’s immanent frame is prepared to contain, but leaves their significance up to readers to interpret for themselves. It speaks in a “subtler language” (Taylor 2024, 33) that does not compel assent but evokes awe. For as MacDonald himself says, “If there be music in my reader, I would gladly wake it. […] If any strain of my ‘broken music’ make a child’s eyes flash, or his mother’s grow for a moment dim, my labour will not have been in vain” (2004, 69).

Works Cited

Attebery, Brian. Stories About Stories: Fantasy and the Remaking of Myth. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Gaarden, Bonnie. “‘The Golden Key’: A Double Reading.” Mythlore 24(3) (2006): 35-52.

MacDonald, George. “The Fantastic Imagination.” In Fantastic Literature: A Critical Reader, edited by David Sandner: 64-69. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing, 2004.

—. The Golden Key. New York: Thomas Y. Cromwell & Co., 1867.

Ordway, Holly. Apologetics and the Christian Imagination: An Integrated Approach to Defending the Faith. Steubenville, OH: Emmaus Road Publishing, 2017. Kindle.

Prickett, Stephen. Victorian Fantasy. 2nd ed. Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2005.

Saler, Michael. As If: Modern Enchantment and the Literary Prehistory of Virtual Reality. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Taylor, Charles. A Secular Age. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2007.

—. Cosmic Connections: Poetry in the Age of Disenchantment. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2024.

Tolkien, J.R.R. Smith of Wootton Major. Edited by Verlyn Flieger. London: HarperCollins, 2015.

—. The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien. Edited by Humphrey Carpenter & Christopher Tolkien. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981.

—. Tolkien On Fairy-Stories. Edited by Verlyn Flieger & Douglas A. Anderson. London: HarperCollins, 2014.

Walton, Heather. “A Theopoetics in Ruins.” Toronto Journal of Theology 36(2) (2020): 159-169.

A book that I think would be enormously helpful in thinking through these questions is Timothy Patitsas' _The Ethics of Beauty_ (St. Nicholas Press, 2019). (There is a substantial sample on Amazon, but of course it's best to buy the book from the publisher.) Dr. Patitsas is a Greek Orthodox theologian who is essentially thinking about how to re-enchant the world, how to reintroduce beauty into it, from the psychological/spiritual healing of traumatized veterans to the revitalization of American cities devastated by urban blight. His approach is both liturgical and practical - he's a great admirer of Jane Jacobs - and while his standpoint is absolutely within Eastern Orthodoxy, he's not interested in convincing people of its truth but in bringing its "beauty-first" approach to bear on certain forms of spiritual and social brokenness. "Start with the gift of theophany, not with mental or ethical or scriptural gymnastics designed to earn the gift."

The book is 700 pages with no index, written in an interview/essay form, and it can be exasperating sometimes, but it's one of the most important books I've read recently. Patitsas has a very original and searching mind. He quotes Lewis from time to time and mentions Tolkien's work in passing as the first experience of beauty for many young people; I think the way these references fit into his general sense of the world would be very illuminating for your work on art, fantasy and meaning.