Apart from Oxford, I can think of few better places to study J.R.R. Tolkien than the University of Glasgow. For one thing, the Centre for Fantasy and the Fantastic is an ideal scholarly and collegial container for cutting-edge research into—you guessed it!—fantasy and the fantastic. For another thing, the historic campus is something straight out of The Lord of the Rings.

With its cloisters, lancet windows, and soaring 278-foot tower, the iconic Gilbert Scott Building looks like the Seventh Circle of Minas Tirith if it were built from sandstone instead of marble and white granite. Surveying the confluence of the Rivers Kelvin and Clyde from its hillside perch, this Gothic fantasia of spires and turrets is generally agreed to be up there with Oxford and Cambridge among the most beautiful university campuses in the U.K. Despite the fact that I’ve lived here for almost 3 years, this kid from small-town South Dakota is always a little gobsmacked when he catches sight of it out his office window.

But while the University of Glasgow was founded in 1451, making it the fourth-oldest university in the English-speaking world, the Gilbert Scott Building wasn’t completed until 1891 – the year before Tolkien was born. In fact, the University only moved to its current location in 1870. The only part of the Gilbert Scott Building which dates back further than the 19th century is a staircase on the western side, which was transplanted from the historic Old College site in the city center. So I misspoke earlier: unlike Oxford or Cambridge, the dreaming spires of the University of Glasgow are neo-Gothic.

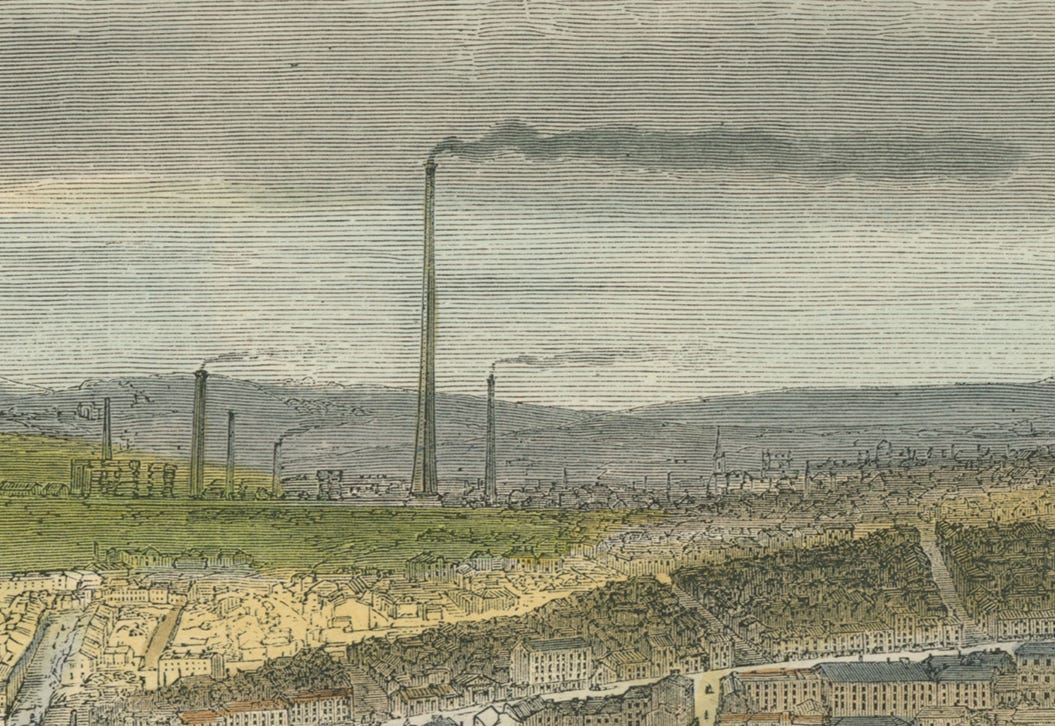

Neo-Gothic, or Gothic Revival, was an architectural movement that emerged during the Enlightenment but really came into its own in the mid-19th century. This was the height of the Industrial Revolution, which was transforming cities like Glasgow into the smoke-belching, worker-exploiting powerhouses of the British Empire. Tolkien grew up near the rolling hills of the West Midlands on the outskirts of Birmingham, another center of the Industrial Revolution. It was in large part the demolition of his beloved countryside to make way for the “infernal combustion engine” (Letters #64) that fueled the love of green and growing things that undergirds so much of his fiction. As he wrote toward the end of his life, “I take the part of trees against all their enemies” (Letters #333).

I’m no historian of architecture, but I am an historian of fantasy and of religion, and it’s not hard to see a kind of Tolkienian rebellion against rampant industrialization in the creative anachronism of Gothic Revival projects like the Gilbert Scott Building. I say creative because the Gothic Revival blends motifs, materials, building techniques, and local styles from a centuries-long period of Western European history known, not always helpfully, as the Middle Ages. Moreover, it brings modern technologies of engineering and urban planning to bear which would have been obviously unavailable to medieval cathedral-builders. If you’ve ever read The Pillars of the Earth, Ken Follett’s novel about the generations-long construction of a fictional cathedral, you’ll have a sense of what I’m talking about.

The outcome of all this re-imagining and recombination is buildings which feel medieval, but aren’t. They are instead medievalist – not unlike fantasy literature of the kind in which Tolkien specialized. Middle-earth is a place where the late 19th-century Shire, Anglo-Saxon Rohirrim, proto-capitalists like Saruman, the fading Mediterranean empire of Gondor, and the timeless Faerie of Lothlórien can all exist alongside one another, wound together with Tolkien’s love of pre-Christian legends, Christian faith, and post-Christian expertise as a philologist, medievalist, and novelist. The result is a Secondary World that feels ancient but is, at one and the same time, profoundly modern.

In that sense, walking across the Glasgow campus feels a bit like entering a Secondary World. As splendidly anachronistic as the Gilbert Scott Building is, Glasgow is still a bustling modern city. The building is hedged on one side by a major street (with everyone on the wrong bloody side of the road – I’m not an American chauvinist on most issues, but this is a hill I will die on) and parking lots on every other. Once you pass beneath its pseudo-medieval portico and pass into the inner courtyard, however, the line between the reality of a modern university and the fantasy of a medieval university becomes blurry at best. For an English-speaking Millennial like me, the wrought-iron lampposts quickly shade into Narnia; the tree in the eastern courtyard resembles nothing so much as the White Tree of Gondor; and the commanding tower problematically but inescapably summons childhood memories of Hogwarts.

It’s an enchanting space, suspended out of time. “You therefore believe it while you are, as it were, inside,” as Tolkien writes in his classic essay “On Fairy-stories.” However, “The moment disbelief arises, the spell is broken; the magic, or rather art, has failed. You are then out in the Primary World again, looking at the little abortive Secondary World from outside.” As soon as you pass back into the world beyond the uni walls, the enchantment fades: city buses and car alarms, modernist and even brutalist buildings right across the road. You aren’t in Middle-earth in the waning days of the Third Age; you’re in the largest city in Scotland and it’s 2025.

As Dimitra Fimi has written, the past is an imaginary world. There’s always a certain amount of creative reconstruction involved in wrapping our heads around an era with which we have no immediate experience. We always run the risk of unduly romanticizing the past – especially when the thing we’re romanticizing never existed. Even our personal pasts are filtered through nostalgia and memory, the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves, reflecting our biases and our blind spots. For instance, the fairytale splendor of Glasgow’s campus elides the exploitation of labor involved in its construction and the processes of colonial extraction which provided the British Empire with enough resources to build such neo-Gothic dreams in the first place.

Yet like Middle-earth, it is, as the aeronaut Giovanni Caproni tells young Jiro in The Wind Rises, “a beautiful dream.”

Thanks for sharing these thoughts and images. I had the good fortune to attend a conference at the University of Glasgow several years ago and was absolutely enchanted by the campus!